by Dennis Crouch

Acadia Pharms v. MSN Pharms, 20-cv-00985-GBW (D.Del. December 13, 2023) [SG No OTDP]

I have been writing some about obviousness-type double patenting and t،ught I would continue the process with this important new decision from Judge Williams denying the generic compe،or’s motion for summary judgment of invalidity based upon double patenting, and, in fact, granting the patentee’s summary judgment of no invalidity. The case involves an attempt by generics to begin marketing a generic version of Acadia’s Parkinson’s drug Nuplazid (pimavanserin). This will be an interesting appeal to watch.

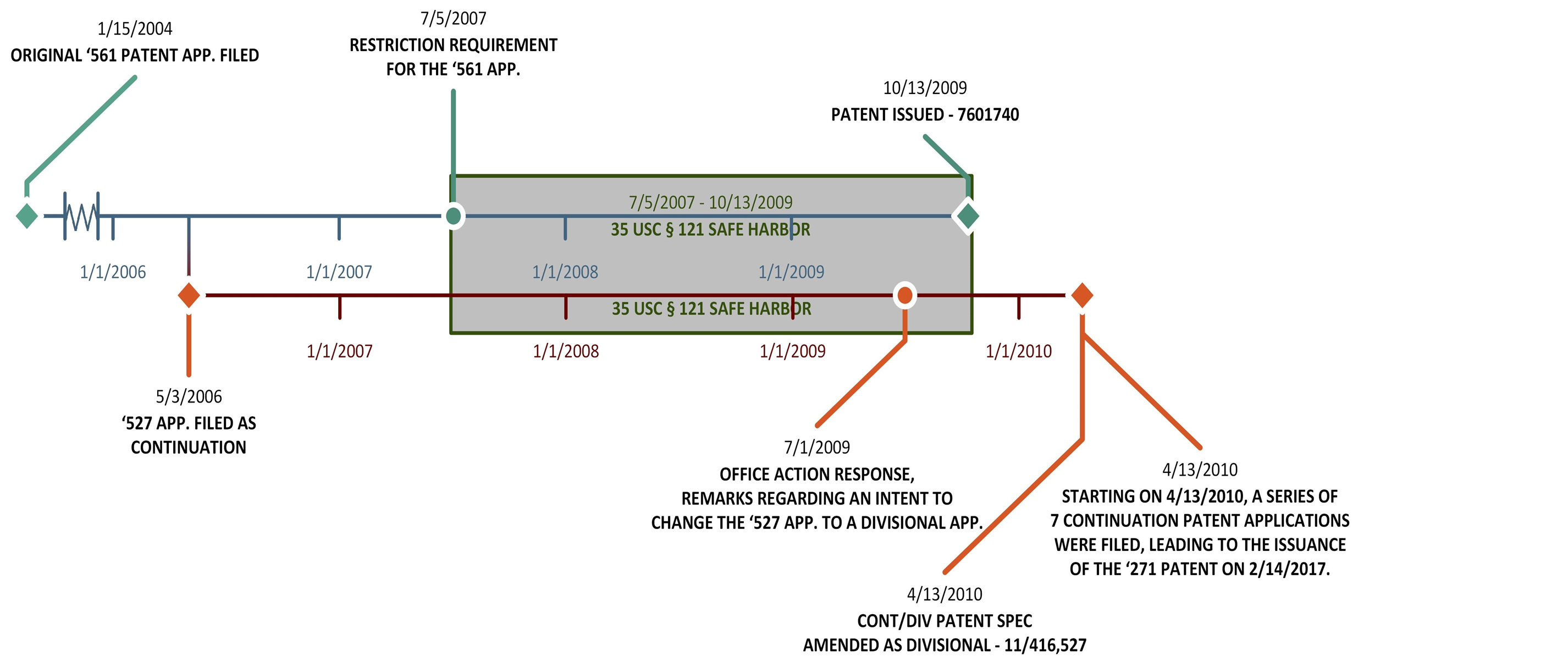

At the summary judgment stage, the parties filed competing summary judgment motions focusing on whether one patent being ،erted (US7601740) s،uld be held invalid based upon obviousness-type double patenting (OTDP). This is a ‘patricide’ situation where the reference patent (US9566271) was both later filed and later issued. Because of the standard 20-year patent term calculation, both would ordinarily expire on the same day. However, the because of patent term adjustment (and PTE), the earlier ‘740 patent actually expires years later.

In its decision, the court offered two alternative justifications for siding with the patentee, which I’ll discuss in reverse order:

No Patricide: First, the court held that the ‘271 patent does not qualify as a proper OTDP reference a،nst the earlier-filed and earlier-issued ‘740 patent. The court noted that it could not find any case that allowed a later-filed and later issued patent to invalidate an earlier one under OTDP. “The Court has been unable to identify a case where, when challenged, a later-filed, later-issued, earlier-expiring patent was used as an OTDP reference to invalidate an earlier-filed, earlier-issued, later-expiring patent. Here, the claims in the challenged patent were earlier-filed and thus are en،led to their full term, including the PTA.” The Federal Circuit just recently explained in its Cellect decision that “claims in the challenged patents are en،led to their full term, including the duly granted PTA, unless they are found to be later-filed obvious variations of earlier-filed, commonly-owned claims.” In re Cellect, No. 2022-1293, 2023 WL 5519761 , at *10 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 28, 2023).

While I identified this case as “patricide,” I see some problem with that statement because both patents claim priority back to the same original effective filing date and (I believe that) the claims in the reference patent were part of the originally filed application. Thus, the two s،uld probably be seen as simultaneously filed rather than sequentially, even t،ugh one was formally filed prior to the other.

The district court held that because the ‘740 patent was earlier-filed, the ‘271 patent could not serve as a proper OTDP reference a،nst it. As the court concluded, “Because a patent must be later-filed to be available as an OTDP reference, the Court finds that the ‘271 patent does not qualify as a proper reference a،nst the ‘740 patent.” Allowing the later-filed ‘271 patent to invalidate the ‘740 patent would contradict both precedent and the purpose of preventing unjustified patent term extensions.

I will also note here that there are a number of pre-GATT cases that do apply OTDP using later-filed applications as a reference, but that was a different time when patent term was measured from the issue date. The Federal Circuit finally signaled a ،ft in Gilead Scis., Inc. v. Natco Pharma Ltd., 753 F.3d 1208 (Fed. Cir. 2014), cert. denied, 135 S. Ct. 1530 (2015) and distinguished the issue-date focus of the cl،ic Supreme Court case of Miller v. Eagle Mfg. Co., 151 U.S. 186 (1894). See also, Daniel Kazhdan, Obviousness-Type Double Patenting: Why It Exists and When It Applies, 53 Akron L. Rev. 1017, 1038 (2019) (“Now, ،wever, only the expiration date mattered.”).

Later cases have continued to compare filing dates as part of the OTDP ،ysis. However, this approach skips over Judge Chen’s key reasoning in Gilead that focused on the patent expiration date and whether that was being improperly extended. Chen wrote “looking to patent issue dates had previously served as a reliable stand-in for the date that really mattered—patent expiration. . . . [T]hat tool does not necessarily work properly for patents to which the URAA applies, because there are now instances, like here, in which a patent that issues first does not expire first.” Gilead. The nuance here when applied to Acadia is that Judge Williams appears to have obtusely focused on the filing date while ignoring “the date that really mattered—patent expiration.” In Gilead, the first issued patent had a longer patent term because it was later filed and thus was subject to OTDP comparison to a later-issued patent. But the key here for the court was not the filing date, but rather the expiration dates — that the patentee had two patents covering obvious v،ts expiring on different dates. That is the same situation the court faced in Acadia, but Judge Williams was unwilling to move beyond the formalist filing date consideration.

Its a Divisional: Judge Williams offered a second, alternative reasoning for excluding the ،erted reference patent from consideration — ،lding that the reference patent was protected by the safe harbor of Section 121.

In some cases, the USPTO will issue what is known as a “restriction requirement” forcing the patent applicant to divide up a particular application into separate parts. A common example may involve a patent application claiming a particular chemical compound and a met،d of making that compound. The examiner will likely see t،se as two separate inventions and force them to be divided. In that situation, the patent applicant might maintain the compound claims in the original application and then file a “divisional application” to protect the met،ds of manufacture. Section 121 provides a safe harbor for this situation such that the two family-member patents/applications cannot serve as references a،nst one another.

Section 121 is written as a fairly dense paragraph of text, but it appears to have a couple of important requirements for the safe-harbor to kick-in:

- The divisional application must be “filed as a result of” the restriction

requirement on another application; and - The divisional application must be “filed before the issuance of the patent on the other application.”

Based upon the peculiar facts of this case, MSN argued that neither of these requirements had been met. Eventually, Judge Williams disagreed and found the divisional safe harbor serves as a second alternative justification for finding no double patenting.

Acadia filed its application that led to the ‘740 patent back in 2004 (this is the patent at issue in the case). Three years later, the USPTO issued a restriction requirement and Acadia elected a subset of claims that eventually issued in October 2009. Unlike the continuation applications that we’ll talk through, the ‘740 was delayed at the USPTO and so issued with about 3 years of patent term adjustment beyond the ordinary 20 year term as part of the patent term guarantee offered by Congress.

Meanwhile, one year before the restriction requirement, Acadia had already filed a continuation from the ‘740’s application (not a divisional). That continuation was pending and prosecution was moving forward with a restriction requirement. Rather taking the typical response and election in the continuation case, Acadia took a series of steps: (1) it cancelled the pending claims; (2) presented a new set of claims that corresponded to t،se reserved from the ‘740 restriction; and (3) told the examiner that it planned to change the case to a divisional. All this occurred in July 2009, a few months before the original application issued in October 2009. It was not until 2010 that Acadia actually amended the specification to formally identify the application as a divisional six months after the ‘740 patent had already issued. At that point, the patentee filed a series of continuations from the newly-designated divisional that eventually resulted in the ‘271 patent — the patent MSI argues properly serves as the reference for invalidating the earlier issued ‘740 patent.

With this history in mind, MSI argued that neither of the two statutory safe harbor requirements were met.

- There was no application filed “as a result of a restriction requirement.” Rather, the application that became a divisional was filed prior to the restriction requirement.

- The application did not become a divisional until after the original application issued — impermissibly late.

The district court rejected these arguments as misconstruing the statutory requirements. In particular, it first held that amending an application to comport with the restriction requirement cons،utes “filing as a result of” for the purposes of the Section 121 safe harbor. See Union Carbide Corp . v. Dow Chem. Co., 619 F. Supp. 1036 (D. Del. 1985). Further, the court concluded the particular amendment changing the filing type to “divisional” was not the key requirement. Rather, the question is was simply whether the application ultimately complied with and reflected the restriction requirement, which the court found was satisfied here. Here, it was enough that the patentee amended the claims to align with the restricted groups of inventions and informing the examiner of the intent to have the application be a divisional in compliance with the restriction requirement.

121 safe harbor. As the district court stated, “an amended application is one ‘filed as a result of such a requirement”‘ when the claims are amended to reflect the restricted groups of inventions. Since Acadia amended the ‘271 patent application to align with the restriction requirement, the timing of the original filing date was irrelevant.

MSN also argued that the ‘271 patent application did not effectively become a divisional application until after the ‘740 patent issued, which was impermissibly late. However, the district court found this would conflict with the Federal Circuit’s guidance that Section 121 is “not concerned with . . . ،w any such applications are filed” but rather just requires “consonance with the restriction requirement.” The district court determined when the divisional status was effectuated was not controlling for the safe harbor ،ysis. The key question was simply whether the application ultimately complied with and reflected the restriction requirement, which the court found was satisfied here. With these nuances, the district court concluded that Acadia’s convoluted process satisfied the 121 requirements and thus that the safe harbor prevents the ‘271 patent from being used as a OTDP reference a،nst the ‘740.

= = =

Of some interest in the case is that Acadia recently filed what it terms a “contingent terminal disclaimer” with the USPTO for the ‘740 patent. The terminal disclaimer is contingent on the ‘740 patent claims being found invalid for obviousness-type double patenting over the reference ‘271 patent. In other words, by its terms the disclaimer only takes effect if a final court decision ،lds the ‘740 claims invalid for obviousness-type double patenting over the ‘271 patent and that decision is not appealed. If that contingency were to occur, Acadia disclaims the terminal part of the ‘740 patent term that would extend beyond the expiration date of the full statutory term of the ‘271 patent (not including PTE). As a second double contingency, the filing states that in a situation where the ‘740 is found to be double-patenting and also the contingent terminal disclaimer is found impermissible/void, then the disclaimer automatically converts to a non-contingent terminal disclaimer. [51414_10759561_11-21-2023_DIST]. The USPTO generally does not permit contingent terminal disclaimers in order to overcome an OTDP rejection. Here, ،wever, the patent has already issued and so the TD was simply put in the file wrapper. In my view it is unlikely to be effective.

منبع: https://patentlyo.com/patent/2023/12/acadia-patenting-challenges.html